Le 17/04/2024

A study of the misunderstandings and misrepresentations of feminism.

Written by : Elena RUGGIERI

As part of the international expansion of the Cercle de Stratégies et d’Influences, we invite you to look at major contemporary issues from a different perspective, with an off-centre viewpoint.

Introduction :

Is paradoxical, if you think about it, that in a world where to be socially esteemed you must follow the rules of the “politically correct”, feminism has increasingly become to be conceived as a negative, extremist, discriminatory and antagonistic concept by both women and men. We have reached the point where many people – and again I want to stress than I am not talking only about men but also women – are not any more inclined to listen to speeches on women’s right or gender equality because they instinctively associate them with men-hating and self-righteous women who advocate the idea of superiority rather than equality.

This happens especially among the new generations, in my opinion, for mainly two reasons:

1. First, they have not clear in their minds what feminism fights for, nor they know the history of this major movement that has unfold in a myriad of different ideas, beliefs and claims throughout its evolution, and, partly, they also perceive all those issues related with gender discrimination as distant, not-so-urgent and as something-of- the-past.

2. Secondly, especially in the last years, they have been repeatedly lectured on these themes in so many different ways and by the most disparate kind of sources – workshops organized by schools and universities, social media ads, brand’s advertisements, training sessions organized by firms – to the point that they automatically reject the discourse without even listening because they are “exhausted” of talking about it.

An additional problem mining the support to feminism is that the more time passes, the more the conceptions, definitions, approaches and ideologies associated with it broaden, so that we are now in a moment where no one is really able to define in a commonly-agreeable manner what feminism is. As a consequence, each of us, mostly based on his/her experience, construct in its mind its own idea of feminism, creating many contradictions and misunderstandings that only make it easier to support anti- feminist causes. For this reason, I think is important to briefly trace back the history of feminism to grasp from which claims it stems out and how and why its ideologies have evolved over time, in order to try to have a clearer idea of its meaning.

Feminism and its historical evolution:

Before entering into the historiography of feminism, I want to stress the fact that here we are talking about the history of occidental feminism; moving to Africa or Asia, feminism’s evolution would probably be described differently. The feminist movement has been commonly explained as divided in different waves, each reflecting a different set of claims. In reality, it should be understood as formed by many sub-movements building on each-other, an intertwinement of values, ideas and people often in contrast with each other, but to simplify the comprehension the wave-metaphor is surely the best tool.

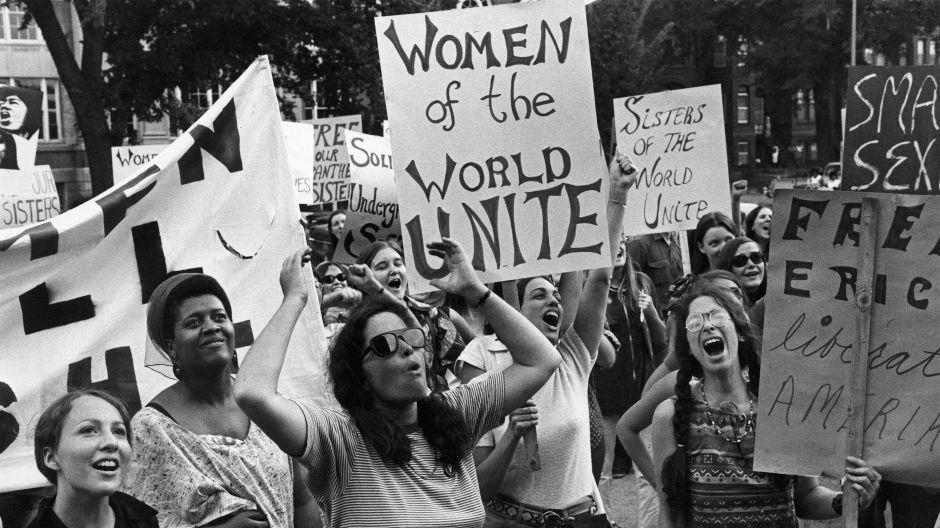

The first wave of feminism goes back to the nineteenth century and was mainly aimed at making the society realise that women are humans, not property. The main claim of this feminist generation was the right to vote, but also the promotion of equality in marriage, parenting and property rights for women. In this stage, feminism was highly political, mostly because in that period women had so few civil rights that they focused their battle on breaking down the “first wall” and gain the basic human rights for which they were fighting. Here there was way less confusion associated with their claims; everyone, if asked “What is feminism?”, would have given similar definitions. Although countries varied a lot in how the movement was organized, they were all aiming to the same goal of equality.

During the 1960s the second wave of feminism hit, and it expanded the debate to a wider set of issues like sexuality, the workplace, reproductive rights, domestic violence, rape issues and legal inequalities. Thus, it lost a bit of the political motive to give space also to the demand of equality beyond the law into women’s real lives – is important to think of the historical context in which we are, where women were still limited in every aspect from family life to the workplace. With the broadening of topics related to the feminist cause, the definition of the latter started becoming blurred and three main types of feminism emerged: liberal – focused on institutional reforms, was aimed at reducing gender discrimination, access to male-dominated spaces and general promotion of equality – radical – wanted a complete reform of the society away from the patriarchal axioms, resisting the belief that women are equal to men – and cultural – advocating the idea of a “female essence” that makes women different from men.

The third-wave instead occurred in the 90s when, thanks to the victories of first and second-wave feminists, women started enjoying more rights. Empowered by this, the main claim among all the different ideas and mini-movements that existed became the one of freedom: women had the right to decide how to live, how to dress, where to work and how to behave independently from the women stereotypes and models imposed by the patriarchal society. Nevertheless, the definition of feminism at this point started encompassing so many different themes and causes that no one was able to state anymore what exactly feminism was fighting for.

Nowadays we are living the fourth wave of feminism that is to be conceived more as a continued growth of the movement rather than a real shift, where even more ideas and movements are emerging – the word “intersectionality” was coined to identify the interconnected nature of social categorizations like race, class and gender, since in the feminist discourse trans rights and black women rights started to conquer more space – and clash with each other to the point that the more feminism unfolds, the more it becomes difficult to give to it a common meaning.

Some misunderstandings on feminism:

Is not to say that feminism should be less inclusive and give space to less voices, it is actually a major achievement the fact that so many different voices are raised as they make the movement itself more inclusive and successful, but to the detriment of its comprehension.

In the last years, also thanks to the ever-increasing use of the social media as a platform where whoever can express itself freely, many anti-feminist posts and comments have been shared that clearly show how people, when talking about feminism, talk about the most disparate kind of things. Monica Pham, a nuclear engineer active on the topic of women empowerment, has conducted an analysis based on comments posted on the Tumblr site called “Women against feminism” and, among the different reasons to oppose feminism that emerge from such comments, three have mostly interested me for the way in which they are easily identifiable in our society: the “equality-for all” claim, the “strong woman” model and the “feminist-man-hater” woman.

The first set of comments can be summarized with the statement: “equality does not equal superiority”, and include all those women that don’t consider themselves feminists – and actually reject it – because they define it as a movement that strives to place the woman above the man. The main reason for this is that they see feminism as calling for the protection of women’s rights, while they believe it should be advocating for the rights of all people regardless their gender. Thus, the main problem for them is that they don’t perceive feminism as calling for equality anymore, and they are strictly linked to the post-feminist belief that we have already reached a point of gender equality so that feminism itself is no longer needed in our society. It’s easy to understand, then, that a person who thinks that feminism is the opposite of an equality- claim and that equality has already been achieved, perceive the feminist cause as useless, old and extremist in its perpetuation.

The second stream of thought revolves around the idea that feminism looks down to traditional female roles like being a mother and a wife. “Being a stay at home wife is my choice!”; “I will not be bullied for choosing traditional values” are only two of the phrases posted on the site. These women perceive feminism as a movement that impose the model of the strong women, that women that has top positions in the workplace – like a manager or a CEO – and call for a complete change of her role in the society.

Feminism, in fact, is so closely linked to the desire of uprooting women from their position as mothers and wives to turn them into strong and independent individuals, that many have started associating feminism to the impossibility for a woman to have a lifestyle dedicated to the care of her family and thus refuse to call themselves feminists. Is obvious that, since many women still prefer to choose motherhood over the carrier, have peculiar religious convictions or are just very conservative, as long as feminism will be associated with the refuse of motherhood and marriage in favour of a carrier and generally to the model of the “strong woman”, more and more women will find it difficult to identify with its claims and will prefer to support anti-feminist positions, or at least they won’t join the feminist cause.

The third argumentations are close to the idea that feminism don’t create equality but rather call for women superiority, but is more focused on the feeling of hatred of men. Many people who try to deal with feminism cannot get past the idea that it is a movement strongly misandrist, that has as ultimate aim the one of bringing down the walls of male dominance. The image of the angry woman that blame men for their inequality and their socially-limited position has become too often representative of what feminism is, and has driven away many women just as much as many men from the feminist cause.

To give a practical example of this we can take the monologue delivered by Paola Cortellesi when she was invited at the “LUISS” university of Rome on the occasion of the start of the new academic year, where she talked about the sexism present in the fairy tales with which most children have been raised – “Snowhite and Cinderella talk about young and naïve girls that are extraordinary beautiful and will be saved from the wickedness of other bad women by the majestic charming prince; and why will he save them? Because they are extraordinary beautiful” was one of the opening phrases of her speech. I believe that the point of her speech was to make people realised that we have been influenced and conditioned by patriarchal ideas that have been imposed on us for so much time and through much more sources than we imagine, direct and indirect ones, and I am grateful that she did because I believe that the first step to overcome such ideologies is to be aware of them. I think her point was to make people think and open their eyes to see the depth of penetration of patriarchy in the Italian society as to make them able to overcome it and live free from it, but when discussing with people that had assisted to this speech, most of them defined it as the “classic, exaggerated, against-men feminist speech” that they were tired of hearing. “We have arrived to the point where also fairy tales are deemed as sexist!”; “Nowadays also at the new academic year’s inauguration we need to talk about women” “If we keep going like this, also a sneeze will be taken as sexist” are just three of the phrases I have heard. Again, Paola Cortellesi’s speech is just one of the million examples of how people misunderstand feminism because are confused on its meaning and, as a consequence, fail to grasp the gist of most speeches supporting its cause.

A contemporary conception of feminism:

I think that most people have lost themselves in the array of claims raised by feminism throughout its historical evolution and have constructed a misleading definition of it based on a mixture of first, second and third-wave claims, neglecting the fact that the beliefs of each wave stem out of the historical context in which they were shaped. Too many people fail to link feminism to the reality and the claims of today, where women conditions, in most of the cases, have drastically improved with respect to those of the first-wave feminism – and it would be an extremism to say that this is not the case – but, still, in Italy in 2023 the 93% of people killed by his/her partner where women; on the world level, one woman out of three declares to have endured psychological violence – namely obsessive control, denigrations and humiliations – in her workplace or at home at least once in her lifetime; in Europe, on a sample of girls be

-tween fourteen and sixty years old, 42% of them declare to be afraid of walking home alone at night because of potential rapists or harassers; a reality where patriarchy is slowly being socially acknowledged, but in Italy almost half of the men interviewed by different journals have admitted that at least once in their life they have endured phrases like “Don’t cry you are not a girl”; “Don’t do that, it’s a girl thing”, “Why are you wearing that girly outfit, are you gay?” or “You can’t wear so many colours on you, you would be taken as gay or worst, as a girl!”.

In light of this, what if feminism today is not about being strong women that reject family care, not about hating all men on earth simply because they are men or about calling for women superiority over men, but rather it is about being free? What if we identify feminism as the belief that each woman, just as much as each man, should be

Maybe, with this conception in mind, it would be easier to commonly agree that is still crucial to talk about feminism, reason on it, acknowledge its claims and the reasons behind them, to arrive, one day, to the point where we don’t need any more to talk and reason about it because its claims will be reached.

Related to the author:

Elena Ruggieri

“Member of the Italian delegation of the Cercle de Stratégies et d’Influences”

Elena RUGGIERI is a third-year student at the University of Rome, Tor Vergata, studying Global Governance (majoring in political science, law and history). She recently joined AIESEC, where she is responsible for projects relating to gender equality (SDG 5). She is currently working with the Sant’Egidio community, helping with the extra-curricular activities it organises for immigrants and children in need.