Le 29/03/2024

To what extent do ancient myths, as products of the human imagination, offer a unique perspective on the relationship between man and nature and resonate with today’s ecological challenges?

Written by : Nicolas GUILBERT

As part of the international expansion of the Cercle de Stratégies et d’Influences, we invite you to look at major contemporary issues from a different perspective, with an off-centre viewpoint.

Introduction :

In the old days, people looked to the sky before making a decision. Mortals, well aware of their smallness compared to Nature, nailed to the ground and silently sharing Icarus’ dream, scanned the sky to interpret divine messages. Not long ago, in the manner of the ancients, certain religious extremists interpreted the appearance of the Coronavirus as an expression of divine anger, a scourge sent by the Creator to punish sinful humans. For some ecologists, however, the calamity was sent to punish mankind for its excesses. So the punishment came not from some god, but from Gaia, Mother Nature, fed up with seeing us pollute her with impunity. For all the harm inflicted, Nature is now seen by some as a merciless deity to whom humans will sooner or later have to beg forgiveness. While the environmental problem is not a myth (and there is no shortage of scientific proof), myths do help to shed light on it. Reading through the lines, it turns out that learning the right lessons from certain myths could have saved us from having to face the problems of the Anthropocene today.

It’s no secret that ecology has now become a major societal issue that cannot be detached from the political sphere. Indeed, as Pierre Charbonnier, philosopher and CNRS research fellow at Sciences Po, points out in his landmark book Abondance et liberté: Une histoire environnementale des idées politiques modernes, after being diametrically opposed for so long, ecology and politics are now unthinkable without each other. In the twentieth century, the ecological struggle seemed secondary to decolonisation, the achievement of economic and social justice and human rights – the “poor relation of social justice”, according to Charbonnier – but at the end of the twentieth century, and even more so at the beginning of the twenty-first century, we saw the emergence of an awareness of the ecological danger facing all human beings and the Earth as a whole. In this sense, we need to bear in mind that this realisation is accompanied by a second awareness: that of the geological dimension of human action. In fact, it is humans who, by enjoying their freedom, have created the monster that is gradually devouring the environment, but they are also the only ones who can theoretically stop it. This is the paradox associated with the concept of the Anthropocene: humanity has endowed itself with such power that it has become a geological actor, but at the same time it has created a monster, an object that is largely beyond the reach of the control capacities it prides itself on. Even Scylla and Cariddi [1] would pale before the monster that humanity has created… By definition, the Anthropocene is a new geological period characterised by the advent of humans as the main force for change on Earth, surpassing the geophysical forces [2]. So, according to scientists, there is a visible gulf between the prospects for political action and the scale of ecological change, which is due to the structure of our systems of governance, which, according to Jedediah Purdy, are “decision-making infrastructures” that “keep us away from the most important issues” and force us to live within “institutions and practices that, while having been refuted by circumstances, denounced as inadequate, nevertheless persist” [3].

The environmental problem is therefore caused by humans. Like myths, to a certain extent. Although ancient myths are often seen as nothing more than fantastic tales, they are in fact stories deeply rooted in the human psyche, reflecting the concerns, fears and aspirations of past civilisations. They offer a fascinating insight into how humankind has interpreted and understood the elemental forces of nature, particularly through Gaia, Zeus and Poseidon. Many of these myths represent the whims of nature, which for millennia have struck fear into the hearts of powerless human populations, warning them to respect the natural balance if they do not want to perish. It’s a way of looking back at the ecological problem: in a world where humans have made abundance their freedom, to the detriment of the natural balance and creating an ecological monster, the consequences for nature are serious, and we have to face up to its whims, those that our ancestors already feared several millennia ago. The “whims of nature” refer to the unpredictable and powerful manifestations of the natural elements, such as storms, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. Human responsibility” implies recognition of our role as guardians of the planet, responsible for maintaining the natural balances necessary for our survival. Human freedom”, as explored by Pierre Charbonnier, lies in man’s ability to transform his environment to satisfy his needs and desires. But what will become of these needs and desires when humans have perished through their own fault?

In this sense, Pierre Charbonnier wrote his work at the dawn of what he himself describes as the third historical bloc of ecological thought: the bloc closest to us, marked by the domination of democratic capitalism and the ever-increasing exploitation of the earth’s natural resources. Gradually, from the birth of political ecology in the 1960s onwards, according to Fabrice Flipo [4], the link between abundance and autonomy was overturned by new thinking: nature was no longer a limitless reserve of wealth, a cornucopia given by Gaia to the goodwill of Man. In The limits to growth [5] published in 1972, the Club of Rome came to oppose infinite linear growth, a year before the first oil crisis, leading to the first reflections on the irreversible changes in ecological conditions in a world that was “getting out of hand” (Charbonnier).

So, against the backdrop of an increasingly worrying ecological crisis, we can ask ourselves to what extent ancient myths, as products of the human imagination, offer a unique perspective on the relationship between man and nature and resonate with today’s ecological challenges.

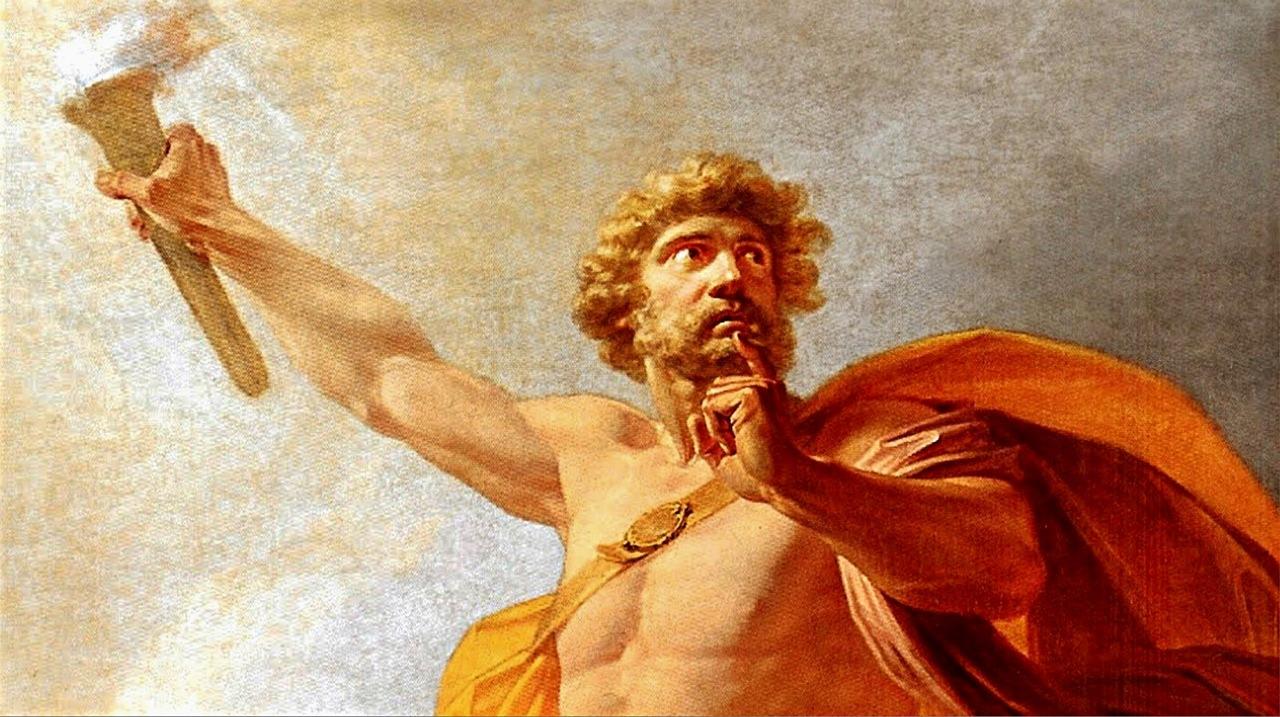

Looking at the ecological problem through the prism of the myth of Prometheus and the mastery of fire

Before turning to the myths, let’s recontextualise and start with a few political reflections. With many governments announcing the start of a period of containment in 2020, the dream of many environmentalists is coming true. Planes are on the ground, cars are off the road and people are forced to stay at home… Greenhouse gas emissions have been reduced by 30% to 35% during the containment period, largely thanks to the curbing of road traffic [6]. However, while nitrogen dioxide linked to road traffic was greatly reduced, AirParif, a French organisation approved by the Ministry of the Environment to monitor air quality in the Île-de-France region, notes that “the impact was less for PM10 and PM2.5 particles, whose sources are both more numerous and not just local”. If we add to this the lack of waste sorting and the increased consumption of plastics of all kinds, leading to an upsurge in illegal dumping, the ecological impact has not been so great. But then, the massive dissemination around the world of videos showing wild animals taking over urban environments has meant that the phrase “nature is reclaiming its rights” has become a leitmotif among (uninspired) journalists. In reality, the underlying idea is to pit the human species, which is inherently malevolent, against nature, which is intrinsically benevolent.

In a way, culture and nature are in opposition. Man, set apart from the animals (even though man is a human animal, as we shall see later), would be a parasite destabilising the natural order of things, oppressing the rest of the living world for his own pleasure or out of arrogance. In this way, all the misfortunes befalling humanity seem to be nothing more than a form of justice. So is nature – as an environmental concept – conscious? In reality, nature is completely ignorant of moral concepts. It is neither benevolent nor malevolent: its only concern is survival. Indeed, intelligent cooperation between living species can exist (and here again there is no shortage of examples), as revealed by certain myths such as those of the Mamertini, Picentes, Hirpini and Lucani [7] about the migrations of Indo-European human animals when they left the Pontic steppes during the third millennium BC, following non-human animals to migrate. The fact remains, however, that the dominant model remains one of predation and competition. From the human point of view, nature, whether animal or plant, is a constant theatre of injustice and cruelty. In the same way that creatures come into the world by devouring their mothers from within, plants are in a perpetual battle for space and access to light. So we are a long way from the idealised vision of a benevolent and just nature. But if, to return to the expression used above, “nature is reclaiming its rights”, then there must have been a confiscation. When did this process begin? The steam engine? Nuclear power? It would seem to be the mastery of fire, which humans are indisputably the only ones to have mastered… thanks to Prometheus…

Without fire, humans would have little weight in the game of natural selection. We could therefore easily consider that, through fire, humanity has violated the natural order of things. Compared with other living species, Mother Nature does not seem to have spoiled human beings. We can’t fly like birds, camouflage like a chameleon or run like a leopard. So what have we got? The domestication of fire. A real revolution. It has brought about a salutary rebalancing of the initial distribution of our species. In the myth of Prometheus, the mighty Titan punished by Zeus for delivering fire to humans, the idea that mastering fire is the first transgression of the “natural order of things” is strongly present. At the sacrifice of Mekone, Zeus gets angry because of Prometheus’s trickery, and he conceals fire, but Prometheus steals it back for humankind. He brings it back to earth in a fennel stalk. Prometheus, commissioned by Zeus to distribute the gifts among the living species, had agreed to delegate this task to his brother Epimetheus. In Protagoras, Plato writes: “And in his distribution, he endowed some with strength without speed and gave speed to the weakest; he armed some and, for those whom he endowed with an unarmed nature, he gave them another capacity for survival. To those he clothed with smallness, he gave wings so that they could flee or an underground lair; those whose size he increased were thereby assured of their safety; and in his distribution, he compensated for the other abilities in the same way” [8]. The brother of the “transmitter of fire”, whose first name means “he who reflects afterwards” [9], thus forgot to give man the attributes of survival. Man is “naked, without shoes, without blankets, without weapons”. It was by virtue of his great wisdom that Prometheus tried to make up for this mistake by stealing the technical knowledge of Hephaestus and Athena, as well as fire, “for without fire there was no way to acquire it or use it, and so he makes a present of it to man.”

So, as we can see from the myth of Prometheus, fire is the prefiguration of man’s transformative power. It is fire, then, that is at the origin of the confiscation of a right to nature. This power enabled man to transcend his initially unenviable condition. However, it also pushed them towards destructive excess, a notion that the Greeks call hubris. Hubris, considered to be a terrible crime, refers to the pride that inexorably pushes men to go beyond measure, or worse, to take themselves for the equals of the inhabitants of Olympus, at the risk of threatening the harmony of the established order… When we talk about the environment, this ‘established order’ can easily be equated with the natural order, the balance of the elements. Prometheus was severely punished for stealing fire and defying the gods. Zeus had him tied up naked on Mount Caucasus [10]. Every day an eagle comes to devour his liver, which regenerates perpetually. Through Pandora, Zeus also punishes mankind by introducing the evils from which humanity suffers, leaving them only hope. A sort of expulsion from the Garden of Eden. According to the same ancient beliefs, mortals guilty of hubris incur the wrath of the goddess Nemesis, the personification of divine righteous anger, sometimes equated with vengeance, sometimes with the balance of power.

The need to respect natural balances

As the myth of Prometheus reminds us, humanity is a complex species which, in order to survive, is obliged to modify an environment on which it is totally dependent. Prometheus is also used by Hesiod to say that we must obey the gods. In fact, from our ecological perspective, we can see the myth of Prometheus as an invitation to find the middle way, that of mètis, a common word used by the ancient Greeks to designate a particular form of intelligence, made up of skill, adaptation and cunning. Humanity must anticipate an ever-changing reality: the Anthropocene. In our introduction, we defined the Anthropocene as “a new geological period characterised by the advent of humans as the main force for change on Earth, surpassing the geophysical forces”. The major problem therefore seems to lie in upsetting a pre-established balance. To preserve the environment, humans need to recognise and respect natural balances. But in reality, it seems that the ancients had already recognised this warning in the myths. The myths of Zeus and Poseidon speak volumes on this subject. Originating in ancient Greece, their myths stand like mythological frescoes capturing the unpredictability and power of the natural elements. By delving into these stories, we embark on a symbolic exploration of the forces that govern the sky and the oceans, embodied by these two major divinities. Zeus, the god of the sky, is often depicted as the master of storms and lightning. His wrath, expressed in devastating storms, symbolises the unpredictable and indomitable nature of the sky. The myths associated with Zeus tell tales of divine wrath unleashed, warning of the devastating consequences of disrupting the natural order. Poseidon reigns over the oceans. While the devastating nature of ocean storms seems obvious, a fascinating article by Hale Güney, entitled “Poseidon as a God of Earthquake in Roman Asia Minor”, also links the god to earthquakes. His wrath manifests itself in raging waves and telluric tremors, reminding mortals of the fragility of their existence in a world shaped by forces far beyond their control. Embodying the duality of fascination and terror that ancient societies felt in the face of natural disasters, most of which have now been scientifically explained, these myths offer a metaphorical representation of nature’s whims and warn of the need to respect nature, which used to be associated with divinities, at the risk of fearing the worst. They bear witness to the human attempt to give meaning to uncontrollable forces by personifying them through all-powerful deities.

In his work, Giambattista Vico [11], one of the most influential theorists of mythology, emphasises the evolving nature of myths, shaped by the collective consciousness over time. The myths of Zeus and Poseidon, evolving over time to reflect the changing concerns of societies, although separated by their respective domains, converge in a common warning: the need to respect natural balances to avoid devastating consequences. These divinities, portrayed as indomitable forces, act as guardians of the limits set by nature itself. They embody ancient wisdom, offering lessons on the complex relationship between humanity and the elemental forces that have shaped human consciousness for millennia.

Rethink human freedom in an era of new ecological demands ?

In the light of the work of Pierre Charbonnier and Arne Naess, the need to rethink our relationship with nature is emerging with urgency. Ancient myths serve as a mirror reflecting the disastrous consequences of failing to respect natural balances, a lesson that modernity seems to have forgotten. Arne Naess, in his book Ecology, Community and Lifestyle, drew the famous distinction between ‘deep’ and ‘superficial’ ecology, and as such is the founder of deep ecology, which has been heavily criticised as being absolutely unacceptable, Malthusian and even neo-pagan, notably by Luc Ferry in Le Nouvel Ordre Ecologique. Ferry distinguishes between two responses to ecological problems. The first is to “protect nature”, which implies changing the way the world evolves in the face of the harmful progress that would have accompanied the human emancipation referred to by Pierre Charbonnier. In this sense, Naess is fundamentally opposed to nuclear power stations, which he sees as a danger to nature. He wants to disengage mankind from the faith of scientific progress, which presents technology as a “miracle”. So we’re not counting on Arne Naess to thank Prometheus for delivering fire to mankind… The second is to realise that the major ecological obstacle is within us and among us. This is the thesis of deep ecology. Naess intends to replace “Man-in-the- environment” with “Man connected with nature”. For him, the environmental problem stems from the fact that “human beings have not yet become aware of the potential they have to enjoy varied experiences in and of nature”. As a result, human beings have a poor understanding of themselves, and it is by digging deep inside themselves and accepting their link with nature that they will be able to act in an ecological manner. This is ‘ecosophy’. For Naess, any other ecological approach can only be ‘shallow’. It would be pointlessly attacking the external effects of the crisis, a theoretical discourse with no consequences, no performative effect: all other ecological thinking sets out ethical rules and foretells disaster, but does nothing to prevent it from happening. His position, as he himself readily admits, is in this sense close to non-violent anarchism. Greek myths highlight this connection, emphasising that man is not only dependent on nature, but interconnected with it. The devastation caused by Zeus and Poseidon highlights the consequences of forgetting this interconnection.

Pierre Charbonnier, writing well after the first emergence of political ecology, seeks to construct a new way of thinking not only within political philosophy, but even within ecological thought. He offers a new framework for understanding how modernity has evolved towards a vision of freedom that is disconnected from ecological realities, when myths remind us, on the other hand, that freedom is linked to the ability to live in harmony with nature, and not to the unbridled exploitation of its resources. Modern thinking, whether liberal or socialist, has always taken the abundance of resources for granted. The exploitation of these resources was part and parcel of the emancipation of human beings and society, without any real consideration being given to the sustainability of these resources. The issue is no longer that of a society built around heteronomistic or autonomistic principles; it is no longer a question of principle, but of the perpetuation of what serves as the basis of all society: nature. The problem can be summed up in one sentence: without nature, there can be no human societies, no political communities.

However, faced with such a huge problem, the responses of the heirs of the modern world are diverse, demonstrating an inability to fully conceptualise the ecological issue and integrate it into their thinking. Some liberals are advocating green finance, while reactionary movements are calling for a return to nature and the land of our ancestors. No clear answer emerges, proof that the environmental issue is struggling to define itself within a constructed philosophy. In the face of this confusion, Charbonnier asserts one thing: an ecological political philosophy cannot be content with being liberalism, communism or any other conception of the world that simply dispenses with the accumulation of wealth. It requires a profound change in the way we conceive of society. In the same way, technology is not a solution. To quote Charbonnier: “Achieving prosperity without growth, to use the title of a famous book, is not the result of a technological solution but of a political change whose historical equivalents can be found in the great technical and legal revolutions that founded modernity and served as a laboratory for our shared ideals”. In the contemporary context, the ecological crisis calls for a fundamental reassessment of our concept of freedom. The myths of Zeus and Poseidon remind us that freedom is not achieved by the irresponsible abandonment of natural constraints, but by a profound understanding of our place in the global ecosystem. The conclusion we are faced with today, at the crossroads of ancient myths and contemporary research, is that freedom can only be sustainable if it is rooted in respect for natural balances. The consequences of the whims of Zeus and Poseidon, illustrated in these myths, should serve as an urgent reminder that our individual and collective freedom is intimately linked to the preservation of the ecological order.

Perspectives :

The teachings of these ancient myths resonate with contemporary ecological challenges, as humanity faces a new geological period characterised by its dominant influence on the Earth, the Anthropocene. Freedom, as conceptualised by the moderns, needs to be revisited today, incorporating a deep understanding of our interconnectedness with nature, invite us to move beyond traditional political paradigms and rethink our society holistically. In the face of the ecological crisis, it is crucial to recognise that individual and collective freedom are intrinsically linked to the preservation of natural balances. The ancient wisdom of myths, evolving over time, continues to warn us against human hubris, calling for a reconciliation with nature rather than its unbridled exploitation. In this quest to rethink our relationship with nature, ancient myths offer us a symbolic mirror to illuminate our path towards sustainable coexistence with nature. Moving towards an ecologically sustainable future requires global collaboration, changes in individual behaviour and profound transformations in our political and economic structures.

As timeless narratives, it is by embracing the teachings of ancient myths that we can work to build a world where human freedom harmonises with, rather than disrupts, natural cycles: we need to find the key to avoiding the devastating consequences of the whims of Zeus and Poseidon in our contemporary reality.

[1] Emmanuel Ferlaino, Le mythe effrayant des monstres Scylla et Cariddi, published on 5 March 2021.

[2] Francois Gemenne and Marine Denis, « Qu’est-ce que l’Anthropocène ? », 8 October 2019.

[3] Pierre Charbonnier, Abondance et liberté, 2020, pages 419 to 425.

[4] Fabrice Flipo, L’enjeu écologique. Lecture critique de Bruno Latour, Revue du MAUSS, 2006, pages 481 to 495.

[5] Dennis Meadows, Donella Meadows and Jorgen Randers, The limits to growth, 1972.

[6] Muryel Jacque, Le confinement n’a été que partiellement bénéfique à l’environnement, publié le 12 mai 2020.

[7] Joseph Rykwert, The Idea of a Town: The Anthropology of Urban Form in Rome, Italy and the Ancient World, May 4, 2011.

[8] Translation from the french text.

[9] Etymology first attested by Hesiod, see Patrick Jean-Baptiste (ed.), Dieux, déesses, démons : dictionnaire universel, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 2016, p. 267.

[10] Lucian de Samosate, Prométhée ou le Caucase, 2015, p. 320.

[11] Almut-Barbara Renger, Between History and Reason: Giambattista Vico and the promise of classical myth, Freie Universität Berlin.

Bibliography :

CHARBONNIER Pierre, Abondance et liberté. Une histoire environnementale des idées politiques. Paris, La Découverte, “Sciences humaines”, 2020.

DE SAMOSATE Lucien, Prométhée ou le Caucase, 2015, p. 320.

FERLAINO Emmanuel, The frightening myth of the Scylla and Cariddi monsters, 5 March 2021.

FILIPO Fabrice, “Penser l’écologie politique”, Volume 16 Numéro 1, May 2016. URL : http://journals.openedition.org.ezpaarse.univ-paris1.fr/vertigo/16993

FILIPO Fabrice, L’enjeu écologique. Lecture critique de Bruno Latour, Revue du MAUSS, 2006, pp. 481-495.

FLIPO Fabrice, “Arne Naess et l’écologie politique de nos communautés”, Mouvements, 2009/4 (n° 60), p. 158-162. URL: https://www-cairn-info.ezpaarse.univ-paris1.fr/revue-mouvements-2009-4-page-158.htm

FORMOSO Bernard, “Pierre Charbonnier, Abondance et liberté. Une histoire environnementale des idées politiques“, L’Homme, 2020/2-3 (no. 234-235), pp. 338-340. URL: https://www-cairn-info.ezpaarse.univ-paris1.fr/revue-l-homme-2020-2-page-338.htm

GEMENNE Francois and DENIS Marine, « Qu’est-ce que l’Anthropocène ? », 8 October 2019.

GENICOT Nathan, “Pierre Charbonnier, Abondance et liberté. Une histoire environnementale des idées politiques“, Lectures, Les comptes rendus, 03 June 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org.ezpaarse.univ-paris1.fr/lectures/41367

GUNEY Hale, Poseidon as a God of Earthquake in Roman Asia Minor, 2015. URL : https://www.persee.fr/doc/numi_0484-8942_2015_num_6_172_3292

JACQUE Muryel, Le confinement n’a été que partiellement bénéfique à l’environnement, 12 May 2020.

MEADOWS Dennis, MEADOWS Donella and RANDERS Jørgen, The limits to growth, 1972.

PATRICK Jean-Baptiste (ed.), Dieux, déesses, démons : dictionnaire universel, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 2016, p. 267.

RENGER Almut-Barbara, Between History and Reason: Giambattista Vico and the promise of classical myth, Freie Universität Berlin. URL : https://jcrt.org/archives/14.1/renger.pdf

RYKWERT Joseph, The Idea of a Town: The Anthropology of Urban Form in Rome, Italy and the Ancient World, 4 May 2011.

Related to the author:

Nicolas Guilbert

“President of the Cercle de Stratégies et d’Influences”

Nicolas GUILBERT is a third-year dual degree student in History and Political Science at Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne and preparing for the Senior Civil Service entrance examination. With international experience abroad, notably at Charles University in Prague, where he specialised in the study of “Religion and Mythology of Sacred Nature”, Nicolas is very keen to open up new avenues of thought, as he does with this article.